The compatibility of faith and reason

One of Newman’s greatest contributions to Christian thinking, and one which guided him in his educational endeavours, concerns the relation of faith and reason in fallen man. He was convinced that the disjunction of academic and moral education was one of the great evils of the age. He saw through the argument that by becoming more knowledgeable, a man would become better morally, while understanding how a people like the English, with no real religious faith to speak of, would resort to such false notions as the supposed moral benefits of knowledge: such an idea, he held, was based on a false understanding of human nature, for it did away with any conception of moral development and neglected the education of conscience.

The whole foundation of Bentham’s utilitarian University College in London was premised on the idea that knowledge does make men better morally; as early as the 1830s, Newman was a consistent critic of this fallacy of the ‘march of mind’.

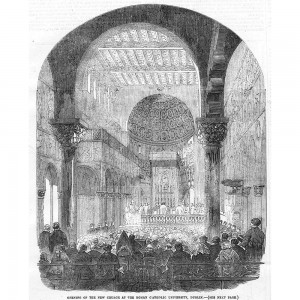

For Newman, the University Church in Dublin ‘symbolized the great principle of the University, the indissoluble union of philosophy with religion’. (‘What I aimed at’)

Newman balances the claims of revealed religion and natural knowledge, explaining that a university, ‘is pledged to admit, without fear, without prejudice, without compromise, all comers, if they come in the name of Truth; to adjust views, and experiences, and habits of mind the most independent and dissimilar; and to give full play to thought and erudition in their most original forms, and their most intense expressions, and in their most ample circuit’. (Idea of a university)

The university man ‘who believes Revelation with that absolute faith which is the prerogative of a Catholic, is not the nervous creature who startles at every sudden sound, and is fluttered by every strange or novel appearance which meets his eyes’. Rather than live in a state of apprehension, ‘he laughs at the idea, that any thing can be discovered by any other scientific method, which can contradict any one of the dogmas of his religion’. (Idea of a university)

The fusion of the secular and religious in education

While educating in a Christian setting, Newman was careful to respect education’s inner autonomy; he understood the relationship between education and religion by recognising that ‘Knowledge is one thing, virtue is another’. (Idea of a university) This is why he could claim that ‘the University is, we may again repeat, a secular institution, yet partaking of a religious character’. (‘Architectural description of the University Church’)

Newman recognises the harmonious fusion of the secular and religious in the education which was introduced in the twelfth century: ‘the germ of the new civilisation of Europe, which was to join together what man had divided, to adjust the claims of Reason and Revelation, and to fit men for this world while it trained them for another’. (Rise and progress of universities)

In the same way he distinguishes in equally stark fashion between a secular university and a fully Christian one: ‘A great University is a great power, and can do great things; but, unless it be  something more than human, it is but foolishness and vanity […] It is really dead, though it seems to live, unless it be grafted upon the True Vine […] Idle is our labour, worthless is our toil, ashes is our fruit, corruption is our reward, unless we begin the foundation of this great undertaking in faith and prayer, and sanctify it by purity of life.’ (‘The secret power of Divine grace’, sermon preached at the Catholic University Church, 1856)

something more than human, it is but foolishness and vanity […] It is really dead, though it seems to live, unless it be grafted upon the True Vine […] Idle is our labour, worthless is our toil, ashes is our fruit, corruption is our reward, unless we begin the foundation of this great undertaking in faith and prayer, and sanctify it by purity of life.’ (‘The secret power of Divine grace’, sermon preached at the Catholic University Church, 1856)

Gratia perfecit naturam

In his last sermon at the Catholic University Church Newman spoke of St Paul as the shining example of those,

‘in whom the supernatural combines with nature, instead of superseding it, − invigorating it, elevating it, ennobling it; and who are not the less men, because they are saints. They do not put away their natural endowments, but use them to the glory of the Giver; […] Thus they have the same thoughts feelings, frames of mind, attractions, sympathies, antipathies of other men, so far as these are not sinful; only they have these properties of human nature purified, sanctified, and exalted; and they are made more eloquent, more poetical, more profound, more intellectual, by reason of their being more holy.’ (‘St Paul’s characteristic gift’, sermon preached at the Catholic University Church, 1857)

A flourishing faith

Since it was taken for granted within both the Established Church and the Catholic Church that university would provide an opportunity for a student’s faith to mature and flourish, Newman did need to persuade anyone about it. For this reason he does not write about it explicitly.

Little is known about Newman the undergraduate and how his faith developed, though he does refer to this in his Apologia; it can also be discerned in his (largely autobiographical) novel Loss and gain.

We are better informed about Newman the tutor and how he saw the task as of spiritual oversight.

Newman the undergraduate

Far from the world of student high jinks and outdoor pursuits, Newman spent his first year buried in books, lectures and private devotions What these devotions were can be deduced from an article he wrote for The Christian Observer entitled ‘Hints to religious students at College’ (October 1822). In the course of suggesting that the religious student should not leave his devotions to the end of the day, he mentions spending half an hour each evening on prayer, meditation, self-examination and the reading of Scripture.

Going up to Trinity College, Oxford at the tender age of sixteen was a chastening experience for the earnest young man of Calvinist leanings, who found himself among sixty undergraduates, all of them older than himself, not over-studious and given to enjoying life. Within a week of arriving, at the tail-end of the academic year 1816/17, Newman’s preconceptions of Oxford were shattered when he attended a wine party and found himself in the company of undergraduates who enthusiastically set about getting drunk. As he would later say, it was the support of Walter Mayers (a teacher from the school he had attended) which helped him through ‘the dangerous season of my Undergraduate residence’, by warning him not to associate with those who were dissipated and instead to seek out select friends – and by urging him to face up to the dangers of residence at Oxford and endure the ‘ridicule of the world’.

Newman the tutor

Newman became a tutor of Oriel College in 1822 and, like most other tutors, took Anglican Orders. When he saw that his calling might be for college rather than parish work he gave up the curacy of St

Clement’s parish, justifying his decision on the grounds that the tutorship was a spiritual office and a way of fulfilling his Anglican ordination vows.

In attempting to remedy the Neglect in Newman’s Oxford he undertook to combine in his own person the teaching offices of public tutor and private.

Along with other Oriel Fellows, John Keble, Robert Wilberforce and Hurrell Froude, Newman came to the conclusion that the search for religious truth could not be separated from the pursuit of goodness, that intellectual training in theology could not be dissociated from religious and moral formation. This can be seen from the careful records Newman kept of his pupils, both public and private, which included occasional allusions to their spiritual progress.

Scattered throughout Newman’s ‘Memorandum Book about College Pupils’ are references to religious matters: in the entry for Osborn he writes ‘I walked with him etc. spoke to him about Sacrament’; for Mozley, ‘hopeful in religion’; for Money, ‘Well behaved’; for Marriot, ‘good religious principles’; and for Stevens, ‘quite ignorant of religion’ one term, and the next, ‘seems well disposed – spoke to him about Sacrament – he had been reading Bp Wilson yesterday on it’.

Rather than a lecturer on books Newman insisted that he was a teacher of men. He considered that ‘a Tutor was not a mere academical Policeman, or Constable, but a moral and religious guardian of the youths committed to him’. Writing of himself in the third person, Newman records that he ‘set before himself in the Tutorial work the aim of gaining souls to God’ and that when he became vicar of St Mary’s in 1828, the ‘hold he had acquired over them led to their following him on to sacred ground, and receiving direct religious instruction from his sermons’. (Memoir, 13 June 1874)

Newman the rector

Undoubtedly the spiritual health of the University was one of Newman’s main concerns as its rector, although it would be a mistake to think of it as something separate from his desire for the intellectual vitality of the University and for the all-round development of its students, as if these three aims were incompatible.

Naturally, Newman made provision for Religious instruction at the Catholic University and he himself preached at the University Church, Dublin.

While he saw it as the task of the University to teach doctrine, it was the task of the collegiate house to nurture religious growth and practice. He laid down that all those residing in the collegiate houses should receive ‘spiritual direction’, usually from the dean or chaplain of the house, and that they should go to confession regularly with one or the other of them. Mass was to be said daily in each collegiate house, which had its own chapel, but attendance was optional.

Religious instruction and Newman’s university

In Michaelmas Term 1855, students of Newman’s Catholic University were required to attend catechetical instructions four evenings a week given by the University Catechist in Creed and Scripture, as well as a course of lectures on the Roman Catechism on Sundays, before High Mass.

Newman ensured that no student could go through the academic course without any direct teaching of a religious character; furthermore, religious knowledge would form part of the subject matter for the exams for degrees.

Rather than sharpen and refine the young intellects (in secular subjects) and then simply leave them to exercise their new powers on the most sacred of subjects, at the risk of making mistakes, the University – Newman felt – was under an obligation to feed these minds with divine truth as they gained in appetite and capacity for knowledge. What it should teach would vary with the age of the students, for ‘as the mind is enlarged and cultivated generally, it is capable, or rather is desirous and has need, of fuller religious information’.

The subject of religion should be treated simply as a branch of knowledge: just as students studied general history, literature and philosophy, so they ought to have ‘a parallel knowledge of religion’ and study sacred history, Biblical literature and Christian philosophy.

As regards sacred history, Newman reckoned the student should have some idea of the early spread of Christianity; the Fathers and their works; the Christological controversies and heresies; the religious orders; the Crusades. ‘He should be able to say what the Holy See has done for learning and science; the place which these islands hold in the literary history of the dark age; what part the Church had, and how its highest interests fared, in the revival of letters’.

As regards Biblical literature, students should be ‘invited to acquaint themselves with some general facts about the canon of Holy Scripture, its history, the Jewish canon, St Jerome, the Protestant Bible; again, about the languages of Scripture, the contents of its separate books, their authors, and their versions’.

As regards Christian philosophy and theology, Newman wanted to confine coverage to a broad knowledge of doctrinal subjects as contained in catechisms of the Church and in the writings of the lay faithful. ‘I would have them apply their minds to such religious topics as laymen actually do treat, and are thought praiseworthy in treating.’ By ‘Christian knowledge in what may be called its secular aspect, as it is practically useful in the intercourse of life and in general conversation’, Newman meant the four ‘notes’ (One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic) of the Church and the ‘evidences’ of Christianity. (Newman to the dean of the arts faculty, June 1856)

‘Half the controversies which go on in the world arise from ignorance of the facts of the case; half the prejudices against Catholicity [or, indeed, Christianity] lie in the misinformation of the prejudiced parties. Candid persons are set right, and enemies silenced, by the mere statement of what it is that we believe.’ What was not satisfactory was for a Christian to say, I leave it to the theologians, or, I will ask a priest. Instead a Christian ought to gratify the curiosity of even those who speak against Christianity by giving them information, because it was generally the case that ‘such mere information will really be an argument also’.

Being well versed in one’s religion

Addressing the young men attending the evening classes of the Catholic University, Dublin, in 1858 Newman said:

‘Gentlemen, I do not expect those who, like you, are employed in your secular callings, who are not monks or friars, not priests, not theologians, not philosophers, to come forward as champions of the faith; but I think that incalculable benefit may ensue to the Catholic cause, greater almost than that which even singularly gifted theologians or controversialists could effect, if a body of men in your station of life shall be found in the great towns of Ireland, not disputatious, contentious, loquacious, presumptuous (of course I am not advocating inquiry for mere argument’s sake), but gravely and solidly educated in Catholic knowledge, intelligent, acute, versed in their religion, sensitive of its beauty and majesty, alive to the arguments in its behalf, and aware both of its difficulties and of the mode of treating them.’ (Idea of a university)

University Church, Dublin

Besides being the natural setting for preaching, Newman wanted the University Church in Dublin to be ‘the place for all the high occasional ceremonies in which the University is visibly represented’, such as degree ceremonies, formal lectures and public acts. The University Church would be an invaluable instrument ‘in inculcating a loyal and generous devotion to the Church in the breasts of the young’, and would serve to ‘maintain and symbolize that great principle in which we glory as our characteristic, the union of Science with Religion’.

Before the University opened, Newman had hoped ultimately to make the University Church and the collegiate houses into a personal diocese, either with the rector as its bishop, or else with the Archbishop of Dublin as its bishop and the rector as its vicar apostolic. Though this remained an idea on paper, his ambitious thinking conveys the conception he had of his new pastoral responsibility.

Newman took upon himself the entire expense of building and furnishing the University Church in Stephen’s Green, Dublin. Defying the vogue for the Gothic style, he chose the form of a Byzantine basilica, which had the merits of functional beauty, lower cost, suitability for the use of Irish marble,  and relative harmony with the surrounding Georgian buildings. The basic design of the church and its decoration was decided on by Newman, and its execution and interpretation entrusted to John Hungerford Pollen, the Professor of Fine Arts. Newman worked closely with him on the plans and the construction, and used his stay in Rome at Christmas 1856 to commission copies of a set of tapestries designed for the Sistine Chapel by Raphael. Just ten months after Pollen had set to work, the University Church was opened on Ascension Thursday, 1st May 1856 with a pontifical High Mass celebrated by Archbishop Cullen.

and relative harmony with the surrounding Georgian buildings. The basic design of the church and its decoration was decided on by Newman, and its execution and interpretation entrusted to John Hungerford Pollen, the Professor of Fine Arts. Newman worked closely with him on the plans and the construction, and used his stay in Rome at Christmas 1856 to commission copies of a set of tapestries designed for the Sistine Chapel by Raphael. Just ten months after Pollen had set to work, the University Church was opened on Ascension Thursday, 1st May 1856 with a pontifical High Mass celebrated by Archbishop Cullen.

The Sunday after the Church opened was a moving occasion for Newman, because for the first time he looked down from the pulpit at the few dozen students from his university attired in academic dress. The student body was nevertheless a minority in the congregation of just over a thousand, as  numbers were swelled by students from Trinity College Dublin as well as a good number of parents present, academic staff and the fashionable element of Catholic Dublin who had come to hear the famous Oxford convert preach. As it was the feast day of St Monica, the mother of the intellectual convert St Augustine, Newman used the occasion to consider her as a type of the Church, ever solicitous for the return of its clever sons, who had rushed out into the world and were now spiritually dead. A chief task of the Catholic University, Newman explained to the congregation, was to shoulder this responsibility of the Church in caring for her student family. More generally, part of the University’s special office was to receive from parental hands those who were leaving home, and to live up to and delight in its well-known designation as alma mater.

numbers were swelled by students from Trinity College Dublin as well as a good number of parents present, academic staff and the fashionable element of Catholic Dublin who had come to hear the famous Oxford convert preach. As it was the feast day of St Monica, the mother of the intellectual convert St Augustine, Newman used the occasion to consider her as a type of the Church, ever solicitous for the return of its clever sons, who had rushed out into the world and were now spiritually dead. A chief task of the Catholic University, Newman explained to the congregation, was to shoulder this responsibility of the Church in caring for her student family. More generally, part of the University’s special office was to receive from parental hands those who were leaving home, and to live up to and delight in its well-known designation as alma mater.

Read a famous quote from this sermon

Read the whole of this sermon, ‘Intellect, the instrument of religious training’

Read the other sermons Newman delivered to students in Dublin:

‘The religion of the Pharisee, the religion of mankind’

‘The secret power of divine grace’

‘St Paul’s characteristic gift’

Three vital principles of the Christian student

‘These may be called the three vital principles of the Christian student, faith, chastity, love; because their contraries, viz., unbelief or heresy, impurity, and enmity, are just the three great sins against God, ourselves, and our neighbour, which are the death of the soul.’ (Rise and progress of universities)

These dangers are likely to be more pronounced in the professorial system, i.e. in a university which washes its hands of the residential side of university life.

A Catholic university today?

‘I have ever held […] that the true education is that given in a Catholic University; but at the same time I have ever held, and have said I print, that necessity has no law’ (‘Memorandum on allowing Catholics to go to the universities’, 21 April 1867)

‘I have, from the very first month of my Catholic existence, when I knew nothing of course of Catholics, wished for a Catholic University’. (Newman to Northcote, 7 April 1872)

What makes a Catholic university?

‘A University is not ipso facto a Church Institution’, Newman argues; like a hospital, it ‘has no direct call to make men Catholic or religious, for that is the previous and contemporaneous office of the Church’. Nevertheless the indirect effects of a university can be religious; ‘As the Church uses Hospitals religiously, so she uses Universities’. In order ‘to secure its religious character, and for the morals of its members, she has ever adopted together with it, and within its precincts, Seminaries, Halls, Colleges and Monastic Establishments’. (First draft of an Introduction to Discourse VI, 16 July 1852)

What follows from this line of thinking ‘is that the office of a Catholic University is to teach faith, and of Colleges to protect morals’. (Second draft of an Introduction to Discourse VI, 23 July 1852)

Newman reminds his readers that, ‘when the Church founds a University, she is not cherishing talent, genius, or knowledge, for their own sake, but for the sake of her children, with a view to their spiritual welfare and their religious influence and usefulness, with the object of training them to fill their respective posts in life better, and of making them more intelligent, capable, active members of society’. (Idea of a university)

This means that when the Pope recommends to the Irish hierarchy the establishment of a Catholic university, his ‘first and chief and direct object is, not science, art, professional skill, literature, the discovery of knowledge, but some benefit or other, to accrue, by means of literature and science, to his own children; not indeed their formation on any narrow or fantastic type, as, for instance, that of an “English Gentleman” may be called, but their exercise and growth in certain habits, moral or intellectual’. (Idea of a university)

But this does not mean that in acting like this the Church ‘sacrifices Science, and, under pretence of fulfilling the duties of her mission, perverts a University to ends not its own […] the Church’s true policy is not to aim at the exclusion of Literature from Secular Schools, but at her own admission into them. […] She fears no knowledge, but she purifies all; she represses no element of our nature, but cultivates the whole.’ (Idea of a university)

Newman argues that, ‘it is no sufficient security for the Catholicity of a University, even that the whole of Catholic theology should be professed in it, unless the Church breathes her pure and unearthly spirit into it, and fashions and moulds its organization, and watches over its teaching, and knits together its pupils, and superintends its action’. (Idea of a university)

The consistency of his approach with the Church’s traditional teaching on the essential unity of religious and secular knowledge was brought out much more clearly in ‘The Tamworth Reading Room’. There Newman states: ‘Where Revealed Truth has given the aim and direction to Knowledge, Knowledge of all kinds will minister to Revealed Truth’. (Discussions and arguments)

‘It is the honour and responsibility of a Catholic University to consecrate itself without reserve to the cause of truth. This is its way of serving at one and the same time both the dignity of man and the good of the Church, which has “an intimate conviction that truth is [its] real ally […] and that knowledge and reason are sure ministers to faith”.’ (John Paul II, Ex corde Ecclesiae, which quotes from the Idea of a university)

Attending a faith-based college/university?

In the United States students can opt for one of around 600 faith-based colleges – or even universities.

Naomi Riley’s God on the quad: how religious colleges and the missionary generation are changing America (2005) is a study of twenty institutions which aim to educate their students in a strong religious philosophy, whether Baptist, Catholic, Evangelical Protestant, Mormon or Orthodox Jewish. The common features of these institutions throw up some challenging questions:

Could I imagine myself living on an alcohol-free campus?

What would social life be like where dating was not permitted in the first year – or even for the full extent of my degree course?

How would I react to being obliged to commit myself to some form of outreach: assisting on a home-schooling scheme, lending a hand at an inner-city social project, visiting the elderly or sick, helping to run summer camps for youngsters, teaching at Sunday (or Sabbath) schools, mentoring English-as-a-second-language schoolchildren?

Would I mind sacrificing academic prestige for an environment which favours human flourishing?

Would such a college/university allow me to explore and grow in my faith?

Do you find this prospect off-putting? Does it sound too constraining? Doesn’t it sound like a ghetto-like existence? One extraordinary and unexpected fact to emerge from Riley’s survey is that most of students graduating from strong faith colleges are married within three or four years.

Attending a secular or non-denominational university

Newman spoke frankly to the leading layman Lord Howard of Glossop when explaining how he viewed the predicament that Catholics found themselves in during the 1870s. The letter has current applicability for those who attend universities which are all but secular except in name.

‘We are driven into a corner just now, and have to act, when no mode of action is even bearable. It is a choice of great difficulties. On whole I do not know how to avoid the conclusion that mixed [i.e. religiously plural] education in the higher schools is as much a necessity now in England, as it was in the East in the days of St Basil and St Chrysostom. Certainly, the more I think of it, the less am I satisfied with the proposal of establishing a Catholic College in our Universities; and I suppose the idea of a Catholic University, pure and simple, is altogether out of the question.’

Newman thought that the bishops should repeal their virtual prohibition of young Catholics attending Oxbridge colleges, and that they should counter ‘what can only be tolerated as the least of evils’ by placing a strong presence Oxford. This ‘should be a strong religious community, which would act as a support and rallying-point for young Catholics in their dangerous position, commanding their respect intellectually, and winning their confidence, and providing quiet opportunities for their being kept straight both in faith and in conduct’.

He remarked: ‘The true and only antagonist of the world, the flesh, and the devil is the direct power of religion, as acting in the Confessional, in confraternities, in social circles, in personal influence, in private intimacies etc etc And all this would be secured by a strong mission worked zealously and prudently, and in no other way.’

Since a large university allowed a student to choose his company, he felt that ‘the open University, when complemented by a strong Mission, may be even safer than a close Catholic College’. (Newman to Howard, 27 April 1872)